During our weekend in "Hopfenland Hallertau" (that grows 25% of the worlds hops) we saw the Hopfen Museum:

Right outside the front entrance the museum had a hops "field" - you can see their size relative to Frau A:

Each row was a different variety of hops, with small white signs identifying the type and characteristics:

For example, "Hercules" has stronger bitterness while the classic Hallertauer is subtler & more aromatic:

Here is a close-up photo of a hops flower:

And a basketful of dried hops:

If you tear a flower apart you can see the golden resin/powder inside, which is the part used in brewing.

The printed information gets into great detail about the different hops/flower varieties... but only in German:

You also get a good view of how the rows are cultivated in the hops field, kinda-similar to asparagus mounds:

Inside, the museum had more hops growing -- probably so that in winter you can still see & smell live bines:

An interesting fact from the Museum plaques: the amount of hops used in brewing "helles" beer today is only one-fourth of the amount that was used 200 years ago (from 400g per hectoliter in 1806, to 100g per hl in 2003).

Our guess: it's a combination of more efficient/stronger extract, less need for preservations, and taste change.

A similar chart showed how farmers have improved the field structures and processes to increase efficiency.

The chart below shows hours per hectare -- was manually intensive even in the mid-1950s, but then wow!

Of course engineering came into play somewhere -- they had examples of early processing machines that separated the flowers from the bines. Interestingly, the first machines were British and US, then Germany caught up:

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, they used simple drying racks for drying the hops flowers, before later constructing more complex drying buildings:

The museum also had old-fashioned presses used to compress dried hops flowers into more efficient shipping bundles/sacks:

As is typical for Germany and Europe, the towns within the Hallertau geography have always been careful to control and market the quality of their product - regional branding. You can see the metal seal press/stamp on the left and labeling template on the right that were used to identify sacks containing true Bavarian hops:

Just an hour away, nearby Nürnberg because the largest hops trading center in the world at one time:

Nürnberg Hops Market, 1914, courtesy of Photo Archive of Nürnberg

Today, Nürnberg is not needed as a hops way-point. Plus, many of the merchants were Jewish and their businesses were ruined during the Third Reich. These sacks contain just dried flowers - resin/powder not yet extracted:

Even though the above bundles are very old, the herbal scent of the hops flowers was still quite strong.

There was surprisingly little on the resin extraction process, perhaps because the focus here is agriculture.

We did learn that many processing firms sprang up in the 1950s, but there are only three large ones today.

The output is usually dry pellets, but also cans of extract/syrup(?) are made as well:

Germany brews a lot of beer, but they grew enough hops in 1900 that they exported 1/3, and today it's 70%!

You can see where all the pellets go to below -- note how much the beer-loving Czechs get! (And Italy?)

In addition to commercial and technical topics, the Hops Museum also had a history of the region and hops cultivation. I found the old books most fascinating: "Hops as brewing material" from 1901. Notice that "Prof" (professor) Braungart wrote the book -- hops has been a long-standing topic of serious study for Bavaria!

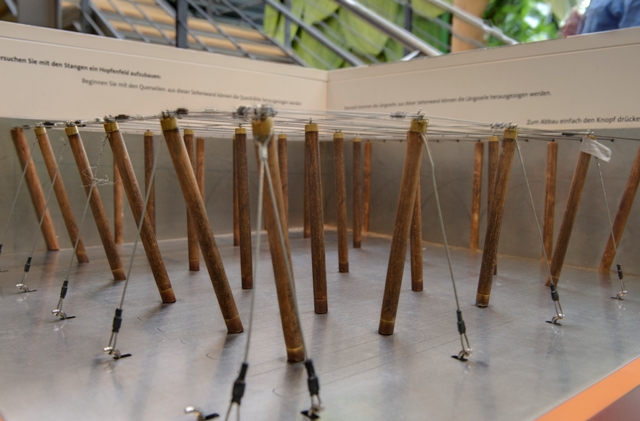

Hops bines are grown on complex wire systems that must stand up to heavy winds. As the wires on which the bines grow are cut during the harvest, they have to be reinstalled each season. A dangerous task, and one that still must be done by hand (today luckily they have things a bit more sturdy than these ladders from the 1920s and 40s!)

But after we (successfully!) strung the wires together in this puzzle version in the museum, we gained an appreciation for how complex the wire system has to be to support everything...not as easy as it looked!

The Museum offers weissbier tastings, and beer & chocolate tastings... but only during the week. (???)

So we didn't (and probably will never) have a chance to try them -- too bad, not very customer friendly.

The entire Museum is relatively small (two floors, takes maybe 1-1.5 hours to see everything). Audio guides are available in English and it really makes for an interesting and educational "beer stop" in northern Bavaria.

And don't forget to get the two local beers from the Museum store, including Lamplbräu (our tour here)!